The Spiritual Kitchen

Do you think that saying “Grace” before a meal is a silly ritual? That it has no real importance and nothing happens? If so, you’d be wrong. Growing up, I was taught to say “Grace” before eating. The long-held American tradition of this Christian act was incomplete without folding your hands, bowing your head, and shutting your eyes as someone older and wiser prayed to Jesus or God the Father to bless the food you were about to eat (and the hands that prepared it). Saying “Amen” at the end was the proper cherry on the sundae, so to speak.

As I grew older, this important ritual became somewhat more relaxed and varied: we held hands with the people on either side of us in an unending chain around the table, we sang The Doxology, we kept our eyes open (*gasp!*) during the prayer, and so on. Very decadent.

It sometimes felt very grand before a meal on an important holy day or special occasion; sometimes, it just felt silly and unnecessary. All the same, it was a constant practice.

Did you know, though, that it is a very necessary thing to do if you wish to be in harmony? I didn’t realize it, either, until I learned about Cleve.

A Man Named Cleve

Our story begins, as these stories often do, with an up-and-coming scientist. He was a young man with a knack for detail and an appetite for knowledge, supplemented with curiosity.

He did not invent the science of galvanic skin response, but he became the expert at using the polygraph (lie detector). Shortly after World War II, he began his career at the CIA as an Interrogation Specialist. He was good at it. He even wrote the book on it.

Grover Cleveland Backster, Jr. (or “Cleve,” for short) eventually became the Chairman of the Research and Instrument Committee of the Academy for Scientific Interrogation. Later, he left the CIA and founded & directed the Backster School of Lie Detection in San Diego, California.

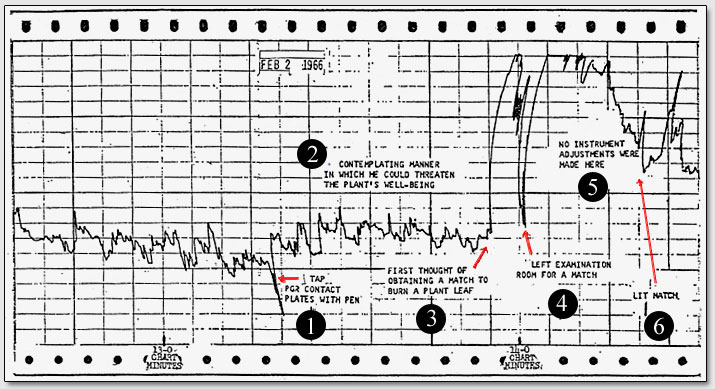

During the 1960s, he let his curiosity lead to tests on plants. He hooked up the polygraph to a large, hearty one (a Dracaena). When he was thinking up ways to get a response, he merely thought, “I’ll try burning a leaf.” Instantly, the polygraph indicated the plant had a huge reaction!

He recounted this in his book Primary Perception: Biocommunication with Plants, Living Foods, and Human Cells:

My whole fascinating experience started on February 2, 1966, around seven o’clock in the morning when I was taking a coffee break after working in the polygraph lab all night. While watering the two lab plants, I wondered if it would be possible to measure the rate at which water rose in one of the plants from the root area into the leaf. I was particularly curious about the dracaena plant because of its long trunk and long leaves. Because of the polygraph examiner school I directed, there were plenty of polygraphs on hand. The polygraph records apparent electrical resistance changes in the skin. [. . .]

The plant leaf resistance, fortunately, fell within the 250,000 OHMS instrumentation range and remained balanced within the GSR circuitry for the 56 minutes that followed. [. . .] I immersed the end of a leaf, that was neighboring the electroded leaf, into a cup of hot coffee. There was no noticeable chart reaction, and there was a continuing downward tracing trend. With a human, this downward trend would indicate fatigue or boredom. Then, after about fourteen minutes of elapsed chart time, I had this thought: As the ultimate plant threat, I would get a match and burn the plant’s electroded leaf.

At that time, the plant was about fifteen feet away from where I was standing and the polygraph equipment was about five feet away. The only new thing that occurred was this thought. It was early in the morning and no other person was in the laboratory. My thought and intent was: “I’m going to burn that leaf!” The very moment the imagery of burning that leaf entered my mind, the polygraph recording pen moved rapidly to the top of the chart! No words were spoken, no touching the plant, no lighting of matches, just my clear intention to burn the leaf. The plant recording showed dramatic excitation. To me this was a powerful, high quality observation.

The plant reacted when he spontaneously and sincerely thought about burning a leaf!

Intrigued, Cleve performed more tests. He discovered that the plant reacted—even rooms away—anytime something was going to be harmed, cooked, or eaten. Boil eggs? It reacted. Pour something down the drain to kill bacteria? It reacted.

However, he also discovered that the plant would not react when his intentions were made known ahead of time. If he approached the plant thinking about how he was going to think of something to make it react, the plant would not. If he made it known that he was going to cook some vegetables, the plant would not react.

He went on to test other things, such as yogurt and human cells. They also reacted to stimulus. In particular, he ran many tests on human cells that were separated by a distance from the person they came from. Those cells indicated they reacted to the emotions of their owner miles away. For one example, watch this video of a television show segment.

What Does This Mean?

The plant got very upset when it sensed it was going to be harmed; therefore, a living plant is aware of and concerned for its own well-being.

If a plant (which we know is alive) gets incredibly “nervous” or “scared” when bacteria (which we know are alive) are going to be killed, then living things are concerned for about other living things.

Seems like these things that are alive are more “alive” than we’ve realized—or have been taught. They all have consciousness.

Continuing on this train of thought: the plant was just as concerned for vegetables or eggs that were going to be cooked. Therefore, the vegetables that were already harvested must still be alive. The eggs are, too, when you really think about it: gestating into chickens is just delayed because of the cool temperatures in which they’re stored.

Therefore . . . foods we eat are aware. They care about the well-being of other living things around them. They are connected. And if something living is distraught about something else being harmed, the food-to-be must itself be very distraught. Yet in contrast, the living things we end up eating can be “okay” with us eating them. To me, these living things we call food understand the circle of life.

Moreover, our own cells react to our thoughts and emotions. When we are distraught, our body reacts. Who wouldn’t want to live with less stress? So, why would you want to eat stressed out food? You are just adding more stress to your insides.

Therefore, dear reader, bless your food when you come home from the market—not after you’ve “harmed” it. Thank the vegetables, eggs, and meat before you prepare and cook them. Thank them for joining you and supporting you on your journey. When you “bless” them, you are calming them. In the end, you and the food you eat are in a state of harmony.

I love you and I thank you. Namasté.